I was getting a cup of tea in the visitors room of the hospice. It was quite late, around 10 o’clock in the evening and I was getting ready to watch over my Dad. My sisters were also there. Y’see, we’d been told earlier that day that Dad was nearing the end of his journey with Motor Neurone Disease and we wanted to be with him, comfort him if needed and do our best to see that the end of the journey came with as few problems, as little anxiety as possible. We wanted Dad to be at peace with his passing.

The door of the visitors room opened and in walked a woman, the daughter of another patient at the hospital, her dad. We exchanged some small talk, spoke of the nervousness of the unknown and expressed how we couldn’t understand how the old men coped so well with their respective conditions.

She explained how the nervousness was often broken by another patient.

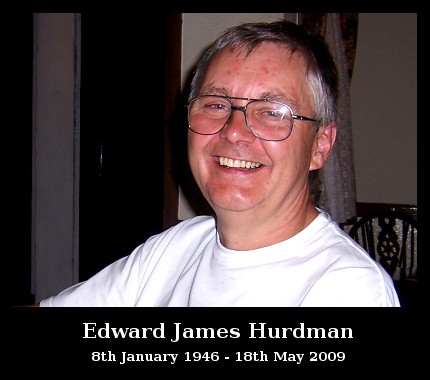

“It can sometimes get a little quiet, but at least we usually get a visitor to break the silence. A guy will often stick his head in the room. A thin guy with grey hair and glasses. He never speaks; he just has a big smile on his face and sticks his thumb up. When we smile and say hi he goes on his way. He might pop in a few times a night. I quite look forward to it”

Of course, that was my Dad and the story sort of sums up his personality quite nicely.

I had some bad news for my fellow hospice visitor, Dad wouldn’t be around that night. Around 9 o’clock that morning his condition had taken a sudden downturn and was unlikely to be with us for more than a few days. As it turned out, that was his last night.

I write this some 3 weeks after Dad’s passing but that encounter with a stranger, with someone whose name I’ll probably never know, brings a smile to my face. It did then, it does now. I’m sure it always will. Dad couldn’t talk, he completely lost his voice to MND about 8 months previous. That didn’t prevent him from being a sociable, likeable guy. He managed to bring a smile to the faces of complete strangers, even as they were consumed with apprehension, lying in bed in a hospice room. Even now he brings a smile to my face as I recall these stories.

Dad was born on the 8th of January 1946 in Saltley, Birmingham. At that time he had two sisters. But another two sisters arrived later and I’m sure all 4 them enjoyed tormenting him in his younger days. I’m led to believe that some of this torment centred around Dad’s favourite toy, Lucy the teddy bear. His oldest sister even buried Lucy in the family back garden. I don’t know if he ever knew what happened to her. However, this toughened Dad up and as he grew up he learned how to execute retribution. His sisters soon learned to be on the lookout for the next prank and I’m sure one of my Aunties still has nightmares about being tied up and left on a shed roof.

Dad learned that the end of the war bought with it many playgrounds, whether it was the bomb sites that littered Saltley or the Ex Army stores that supplied him with military electronics to experiment with. He used some of these electronics to build a telephone line between his bedroom, and a friends bedroom two doors away. He also used them to build an amplifier which burst into flames as he was asking his friend (via the improvised telephone) for advice on making it work, setting fire to his mothers curtains as it blew.

As you may have guessed, my Dad was a curious youngster. His curiosity didn’t end with electronics. He and his friend had read about the engineering behind the jet engine and decided that it was a most simple design. So simple in fact that they could build one. What they built wasn’t so much a jet engine, but more a flame thrower which almost destroyed a hedge. It appears to me that it was only good fortune that prevented Dad from doing a better job of levelling Saltley than Hitler.

It was this curiosity that nearly landed him and his friends in a whole barrel full of trouble. While climbing over a train carriage parked on a railway sidings they found a control wheel. There was much discussion about what this wheel might do after all, a carriage on tracks has no need of a steering wheel. And even if a steering wheel was necessary, it would be on the engine. They decided to turn the wheel, see if the feel of it unlocked its mystery. They gained a clue to it’s purpose as the carriage began to roll down the hill. It was a brake. There was much frantic turning of the wheel in the other direction bringing the carriage to a halt before scarpering.

This sense of adventure he encouraged in myself and my sisters. During the summer holidays, back when I was a school kid and while most of my friends were sat in front of the TV, I was encouraged to visit places on my bike. While I was off visiting attractions such as castles with my bike, my friends were held back by parents who were not quite so good at assessing risk and allowing their children to take some. Dad’s sense of adventure is something that stays with me now and has shaped my interests. It’s something that I will always be grateful for..

Dad met my mum when he was 18 and she 2 years younger. I don’t know too much about this part of their lives. I know they got on quite well because 6 years later I sort of made myself known and they, err, had to get married. 6 months later, I was born.

They lived in Bridge Road for the next 18 months, then moved to Great Barr where they stayed for the rest of their lives.

Both Dad and Mum wanted a larger family and 5 years after my birth my sister Sue arrived, 11 years later Vicky turned up. Like Dad, I was being ganged upon by sisters and Dad was probably quite pleased that at last, it was someone else’s turn.

Dad’s interest in electronics didn’t wane, on leaving school he embarked on a career of electronic servicing spending most of his life repairing TV, radio and video recording equipment. During the 80’s he bought his own TV shop in Erdington, not far from the hospice he stayed in. During one of his visits to the hospice we took a trip of nostalgia and had a look at his shop which is now converted into flats. Towards the end of his career he worked for Wolverhampton New Cross Hospital, repairing medical electronics. He was particularly proud to work for the NHS and felt it a civic duty, a responsibility he took very seriously.

Dad never lost his sense of adventure. With a friend he started parascending and eventually formed a club. Indeed I was first strapped into a parachute and sent several hundred feet into the air at the age of 13, much against my will. Dad just wanted me to share his interests, even if that meant a traumatised childhood.

He enjoyed life up until the moment my mother passed away in 2006. He never really got over mum’s passing but he worked to honour her memory. We decided to cycle from John O’Groats to Land’s End to raise funds for the British Lung Foundation who had supported Mum through her illness. He wanted an apt name for our cycle team and it was decided we’d cycle under the banner of Sheila’s Wheelers. Though Dad hadn’t been on a bike for 35 years or so he trained hard and in doing so become quite a cycle nut. He cycled with the North Birmingham CTC regularly until his illness made this impossible. His training paid off and he cycled the entire length of the country with energy spare to enjoy a short break. The fund raising exercise raised over £4000. The ride is something he’d talk about to anyone who’d listen, not just because it was an achievement he was proud of, but because it was done in Mum’s name. For him, that was everything.

Shortly after the cycle tour, Dad blacked out at the wheel of his car. He was fortunate not to be injured (and more importantly not injure anyone else) and crawled out of his car as it lay on it’s roof. Following a short stay in hospital he was diagnosed with epilepsy which the drugs controlled very well. However, the blackouts didn’t bother him as much as his speech which developed a slur. The Neurologist dismissed the slurred speech and concentrated on his blackouts but back at the hospital he worked at, a Nurse he repaired equipment for grew concerned about his condition and organised an appointment with the Neurologist there.

I was with him when he was given his diagnosis and the words “Motor Neurone Disease” brought with them a minute’s stunned silence. When Dad broke the quiet it was to ask how long he might expect to live. “Up to 2 years”, was the reply. Dad’s next statement was about Mum but then for Dad, it was always about Mum. He said that Mum had been brave with her illness. I said at the time that Dad would be brave too, but I had no idea that he’d be brave beyond the boundaries of heroic.

Y’see, Dad just got on with it. Of course, he was apprehensive about what might happen to him and we discussed this a number of times. But for the most part, he just got on with it. For a start, he went straight back to work following diagnosis. I tried to take him home so he could let the news sink in but he was having none of it. In the canteen at his work I pleaded with him to take the day off but he said that the cup of tea we’d just sipped gave him enough thinking time and he wanted to get back into work. I felt like going home, I needed it to sink in but Dad took it almost in his stride.

I lost count of the number of people who took me to one side and told me that if it wasn’t for Dad’s obvious signs of illness they’d have no idea he wasn’t well. He was always smiling and carried on going to the pub and club even after he could no longer swallow his drink. His Guinness by this time, was poured into his feeding tube (and more often than not on his trousers, the seat and floor too as he lost the dexterity in his fingers). For people who hadn’t known of Dad’s illness this often became a talking point and drew many questions which I had to answer of Dad’s behalf. I was proud of how Dad was never ashamed to whip his feeding tube out in public and never let it stop him enjoying his social life. In fact, give him half a chance and he would show you his feeding tube, whether you wanted to see it or not. I think he got a perverse satisfaction from the horrified reaction he got from some people.

I was often told that by the people who knew him that they had no idea how Dad managed to remain so content and so active in spite of his illness. I understood what they meant; I’m still staggered by Dad’s refusal to give in to the disease and how he just plodded on, just carried on being Dad.

There are aspects of the Disease that I’ll never come to terms with. That disease robbed us of our Dad before it took him from the world. Before Dad lost his speech entirely we noticed the onset of dementia. Around 5% of MND sufferers are affected by dementia, and my old man was one of them. For the most part he was fine but he did have trouble learning new things, his attempt to learn sign language so that he could communicate after losing his speech was futile. He also developed trouble writing because of the dementia. He developed a sort of extreme dyslexia and the words he wrote were a random collection of letters, but they seemed to make sense to Dad and looked at us as though we had a reading difficulty. Dad was able to go out and have a laugh with us or let us know if he was unhappy or wanted help, but we felt that sometimes, he was unable to communicate any worries he might have had.

Dad went into the John Taylor Hospice in Erdington on the 14th of May for a couple of weeks respite care. His condition changed quite suddenly and dramatically on the 17th of May. He slipped away painlessly and peacefully, with his 3 children at his side, holding his hands and stroking his forehead on the morning of the 18th of May. Also there was Dan, his soon to be son-in-law, one of his sisters - Val and his niece Michelle, all of whom had helped care for him as his illness had got a little too much for him.

As far as these things go, it was perfect. It almost seemed that the end, just like his illness was on Dad’s terms, he didn’t let any of it control him.

And that’s how Dad “got cracking” for a final time.

Gazza

Back to News